“אמר רבי יוחנן משום רבי שמעון בן יוחי כל ת”ח שאומרים דבר שמועה מפיו בעולם הזה שפתותיו דובבות בקבר

Rabbi Yochanan said in the name of Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai: The lips of a [deceased] scholar move in the grave when his teachings are said in his name.

”

Plagiarism, it seems, has never been so popular. Remember How Opal Mehta Got Kissed, Got Wild and Got a Life, the 2006 debut novel from Harvard undergraduate Kaavya Viswanathan? The author had plagiarized several passages from others (including Salman Rushdie) and the publisher Little Brown recalled and destroyed all its unsold copies. It's not just authors; politicians plagiarize too. In 2013 the German minister for education resigned amid allegations she had plagiarized her PhD. thesis, and last year Senator Jon Walsh of Montana had his Master's Degree revoked by the US Army War College which determined that it had been plagiarized. (Walsh dropped out of the Senate race as a result of the scandal.)

Plagiarism. It's not just for authors and politicians. Retraction Watch has reported at least 268 academic papers that were plagiarized. Plagiarism has become so pervasive in academia (and the need to report it has become so important) that a recent paper paper in Ethics & Behavior outlines advice for academics considering becoming plagiarism whisleblowers.

This seems to be a very good era in which to remind ourselves - and our students - that the full and proper attribution of the work of others is a core Jewish value.

Sadly, Jewish literature has a many examples of plagarism, improper attribution, and other infractions of publication etiquette. We are going to look at four of these. They are all different, and their ethical breaches are not to be equated, but they are reminders of the responsibility of those who publish to check, double check, and attribute.

1. Partial or inaccurate citation

Inaccurate citation is a relatively lightweight probem, but it's a problem nevertheless. The English language Schottenstein Talmud, published by ArtScroll, chose a censored text of the Talmud as the basis for its translation project. (Full disclosure: I enjoy the Schottenstein Talmud, and study from it each day, God, bless it). As I've pointed out elsewhere, this was a sad choice, and a missed opportunity to return the text to its more pristine (and more challenging) state.

One example of ArtScroll's decision is found very early on in Berachot (3a). There, the original uncensored text records a statement said in the name of Rav: אוי לי שהחרבתי את ביתי ושרפתי את היכלי והגליתים לבין אומות העולם

Woe is me [God], for I destroyed my home [the Temple], burned my Sanctuary, and sent [the Jewish People] into exile among the nations of the world.

However, the editors of the English ArtScroll Talmud chose to use a censored text in which an additional phrase was slipped in by the censor: אוי לבנים שבעונותיהם החרבתי את ביתי ושרפתי את היכלי והגליתים לבין אומות העולם

Woe to my children who sinned, [and hence made me, God] destroy my home [the Temple], burn my Sanctuary, and send them into exile among the nations of the world.

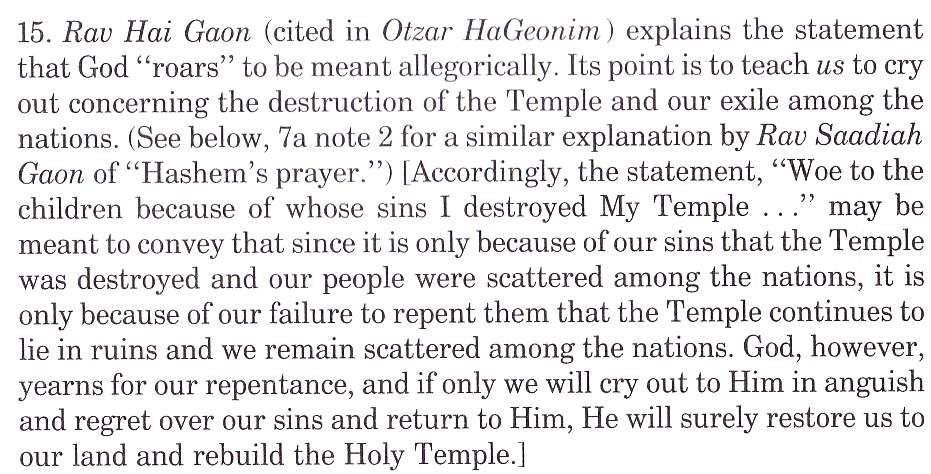

Here is a version of the uncensored text- the one that ArtScroll could have used. As you can see, the censor's additional text is not there:

Then, to compound the error, the ArtScroll Talmud addes a footnote explaining the metaphorical meaning of this erroneous text!

Schottenstein Talmud, Mesorah Publications, Berachot 3a

To be clear: ArtScroll did not plagarise anything, but they should have done a better job of quoting the text accurately. After all, isn't that what Rabbi Yochanan taught us to do? Had they done so, the lips of the great sage Rav, whose teachings were improperly amended by the censor, would again "move in his grave".

Now on to more egregious issues - hard core palgarism.

2. Plagiarism in part

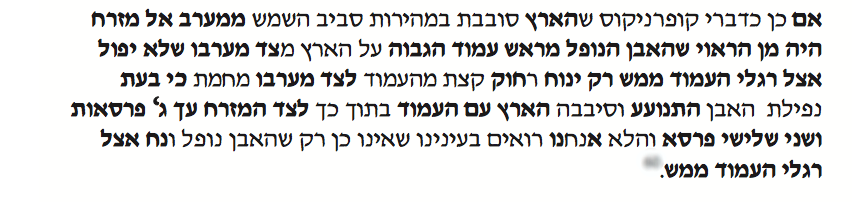

Sometimes another author says it just right, and uses language in so perfect a way that others will want to claim it as their own. One example of this is found in the 500 year long debate over whether Jews could believe in the Copernican model of the solar system in which the sun was stationary. In the late nineteenth century Reuven Landau (c. 1800-1883) took a hard core conservative position against this model. He found it to be existentailly threatening, and argued that because humanity was the center of the spiritual universe, it must live in the very center of the physical one. But rather than outline his claims in his own words, he stole from the very widely read Sefer Haberit, an encyclopedic work that had been published some one hundred years earler. Here is an excerpt from Landau's text, in which he raises what he believes to be scientific objections to the Copernican model. The bold text shows where the text is identical to Sefer Haberit, first published in 1798.

If it is as Copernicus has written, and the earth circles the sun at great speed from west to east, it would be the case that a stone which falls to the ground from the top of a high tower on its western side should not land exactly at the foot of the tower but rather should come to rest slightly to the west of the tower. For while the stone is in free-fall, the earth together with the tower have moved in orbit to the east, by three and two-thirds parsa’ot. Yet we see with our own eyes that this does not occur. Rather the stone falls and comes to rest precisely at the foot of the tower.

Quite simply put, Landau stole from Sefer Haberit. A simple attribution was all that was needed. And it was not there. (You can read more about this plagarism here, and more about Sefer Haberit in my book, and in this recently published work from David Ruderman)

Well, you say, that's not quite right. but it's not too bad either. Well, here comes full, unadulterated plagiarism.

3. Plagiarism in full: Stealing an entire chapter, word for (almost) word

In 1788 in Berlin, Barukh Linda (not to be confused with the plagiarist Reuven Landau) published a small encyclopedia for children called Reshit Limmudim. In it, Linda carefully explained the heliocentric model of Copernicus and how the planets moved around the sun. This book became, in the words of the historian Shmuel Feiner the “most famous, up-to-date book on the Hebrew bookshelf at the end of the eighteenth century,” And then, a year after it was published a Rabbi Shimon Oppenhiemer, living in Prague, stole from it.

Oppenheimer (1753-1851) objected to the claim that the earth revolved around the sun, and in 1789 in Prague he published Amud Hashachar in which he detailed his opposition. But rather than use his own words, he stole, word for word, the descriptions of the solar system from the pro-Copernican Reshit Limmudim, carefully leaving out the bits that supported Copernicus. In a move that pushes hutzpah to a new level, Oppenheimer even published a moving poem as if it had been written to him. However, the poem was a dedication to the real author Linda - from Naphtali Herz Wessely. Oy.

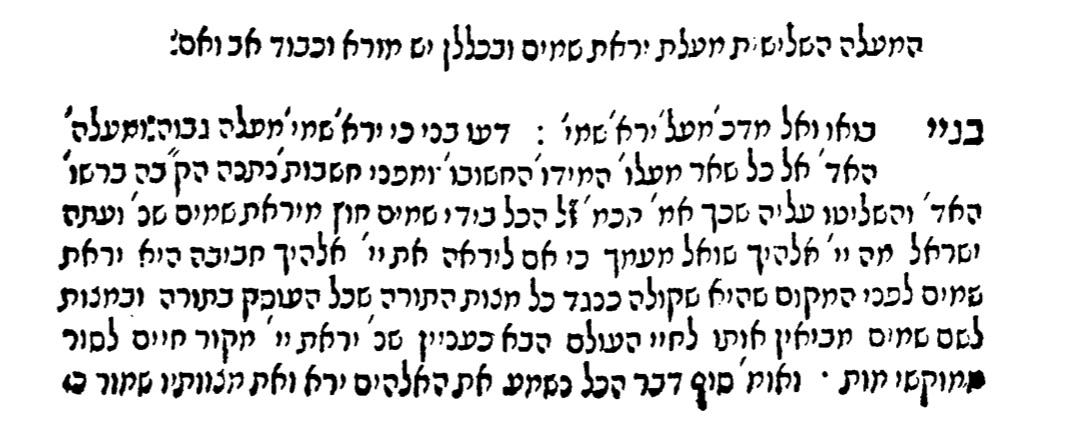

Had enough of Rabbi Oppenheimer? There’s more. When it came to plagarism, this Rabbi Oppenheimer was a repeat offender, (enough perhaps to earn a special mention in a Jewish Retraction Watch). Because in 1831 he published Nezer Hakodesh, a book on religious ethics (I'll say that again in case you missed it - it's a book on religious ethics)...which he plagarized from the 1556 work Ma'alot Hamidot ! Here's a random example so you can see the scale of the plagiarism.

מעלת המדות, 1556

נזר הקודש 1831

There is a fascinating end to the story. The famous Rabbi Yechezkel Landau (that’s the third Landua/Linda in this little post –sorry), head of the Bet Din in Prague, banned Oppenheimer from printing further copies of Amud Hashachar, but not because it was plagarized. Rather, Chief Rabbi Landau objected to the book’s frontispiece, in which Oppenheimer described himself as “The great Gaon, sharp and famous, the outstanding investigator Shimon”. Read it for yourself:

First edition of עמוד השחר, Prague 1789. From the Jewish National and University Library, Jerusalem

In his rebuke, the head of the Bet Din made no mention of the fact that sections of the book were plagiarized, even though this information was widely known. Oppenheimer proceeded undeterred, and published a second edition of his plagiarized and anti-Copernican work – although he was “honest” enough to remove the stolen poem praising his book - a poem that had originally been written by Naphtali Herz Wessely in praise of Lindau’s Reshit Limmudim.

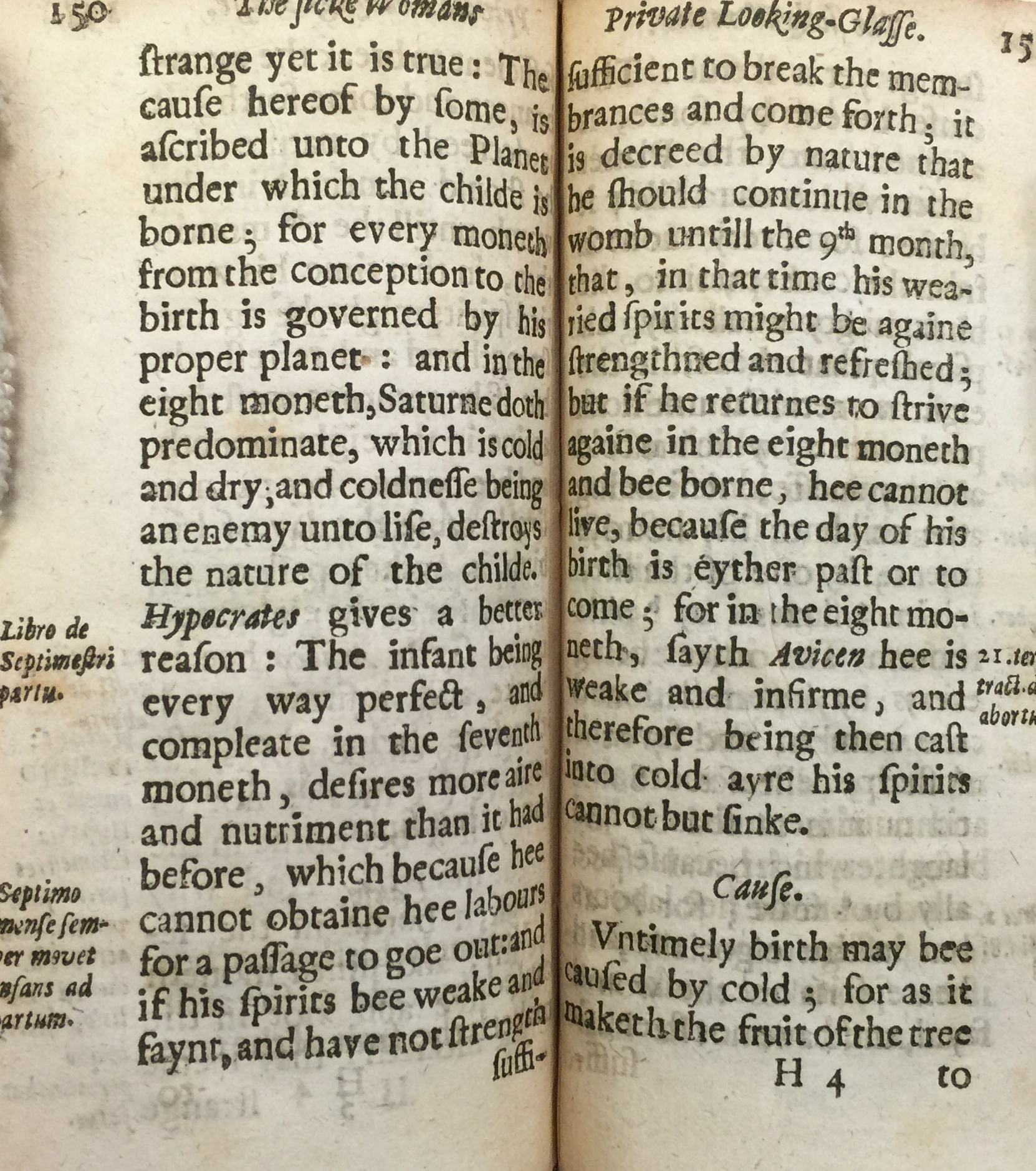

4. Incomplete quotation of a passage

Our last example of plagiarism and citation misuse is again from the ArtScroll publishers, though this time it’s a little more serious than their using a censored manuscript. This time Arscroll is itself the censor.

In their new edition of the Mikra’ot Gedolot, (or, as they call it, Mikra'os Gedolos) the editors have censored an entire passage from the commentary of the great eleventh century French scholar Shmuel ben Meir, known as the Rashbam , without any indication that they have tampered with the text. In a famous passage, Rashbam claimed that – contrary to normative Jewish thought, the twenty-four hours of the Jewish day should begin at sunrise, and not after sunset, as is our practice. This antinomian position seems to have been too much to share with its readers, so ArtScroll just expunged it.

Here is the Rashbam as it appears in the new ArtScroll edition:

חומש מקראות גדולות בראשית. ארטסקרול–מסורה 2014. The red arrow indicates censorship of the Rashbam.

And here is the original text of the Rashbam with the censored text in bold.

ד) וירא אלהים את האור - נסתכל במראהו כי יפה הוא. וכן ותרא אותו כי טוב הוא, נסתכלה במשה שנולד לששה חדשים כמו שמואל לתקופת הימים וראתהו כי טוב ויפה הוא שנגמרו סימניו וצפרניו ושערו, ותצפנהו שלשה ירחים, כלו' עד סוף ט' חדשים שהרי ראתהו וידעה שהוא טוב ויפה בסימנים, שאינו נפל

ויבדל אלהים בין האור ובין החשך - שי"ב שעות היה היום ואח"כ הלילה י"ב. האור תחלה ואח"כ החשך. שהרי תחלת בריאת העולם היה במאמר יהי אור. וכל חשך שמקודם לכך דכת' וחשך על פני תהום לא זהו לילה

ה) ויקרא אלהים לאור יום - תמה על עצמך לפי הפשט למה הוצרך הקדוש ברוך הוא לקרוא לאור בשעת יצירתו יום? אלא כך כתב משה רבינו, כ"מ שאנו רואים בדברי המקום יום ולילה כגון יום ולילה לא ישבותו, הוא האור והחשך שנברא ביום ראשון, קורא אותו הקדוש ברוך הוא בכ"מ יום ולילה. וכן כל ויקרא אלהים הכתובים בפרשה זו. וכן ויקרא משה להושע בן נון יהושע, האמור למעלה למטה אפרים הושע בן נון, הוא אותו שקרא משה יהושע בן נון שמינהו קודם לכן משרתו בביתו, שכן דרך המלכים הממנים אנשים על ביתם לחדש להם שם כמו שנאמר ויקרא פרעה שם יוסף צפנת פענח, ויקרא לדניאל בלטשצר וגו'

ולחשך קרא לילה - לעולם אור תחלה ואח"כ חשך

ויהי ערב ויהי בקר - אין כתיב כאן ויהי לילה ויהי יום אלא ויהי ערב, שהעריב יום ראשון ושיקע האור, ויהי בוקר, בוקרו של לילה, שעלה עמוד השחר. הרי הושלם יום א' מן הו' ימים שאמר הק' בי' הדברות, ואח"כ התחיל יום שיני, ויאמר אלהים יהי רקיע. ולא בא הכתוב לומר שהערב והבקר יום אחד הם, כי לא הצרכנו לפרש אלא היאך היו ששה ימים, שהבקיר יום ונגמרה הלילה, הרי נגמר יום אחד והתחיל יום שיני

This censorship of the Rashbam is not unique to ArtScroll. It exists in other standard printings of Mikra'ot Gedolot, like this one from Machon Hama'or, (Jerusalem 1990), although not in the Torat Chaim from Mossad Harav Kook.

Marc Shapiro, who brought this to the attention of Jewish world, has called for ArtScroll to give a full refund to any one who purchased these censored copies. And he is absolutely correct. A recent academic editorial noted that improper quotation is a type of plagiarism; like complete plagiarism, this selective quotation strips ownership away from the original author, and leaves in its wake a text never intended.

THE need for recognition

In his recently published autobiography, the British comedian John Cleese (of Monty Python and Fawlty Towers fame) recalls how he reacted the very first time that he was recognized after a stage performance. As he walked home, a family who had been in the audience pointed at him and waived. It was by all accounts a small gesture, but Cleese recalled its effects in detail even fifty years later:

I can still remember the sudden feeling of warmth around my heart that swelled and swelled and lifted my spirits. It is as though I had been accepted into a new family, and acknowledged as having brought them something special that they really appreciated. It was only a moment but it was wonderful, and they didn't even know my name...in today's celebrity culture it must be hard to imagine that a tiny moment of recognition like that could feel so uncomplicated and positive...

The need for recognition is not a vice or a character flaw, but a profound human need. To ignore it is not just an oversight but an act of neglect. The rabbis of the Mishnah and the Talmud understood the corollary: that to attribute is to nourish. To acknowledge the creative act of another person is a kind of blessing, like those required before eating, or on seeing a beautiful vista. Blessings and citations acknowledge the creative impulse in others, and so make the world a little bit better. They are redemptive. As this Mishnah taught:

“ כל האומר דבר בשם אומרו מביא גאלה לעולם, שנאמר (אסתר ב), ותאמר אסתר למלך בשם מרדכי

Whoever cites something in the name of the person who originally said it, brings redemption to the world. As the prooftext states - “And Esther told the King in the name of Mordechai...””