קידושין טז, ב

בן תשע שנים שהביא שתי שערות שומא מבן ט' שנים ויום אחד עד בן י"ב שנה ויום אחד ועודן בו שומא ר' יוסי בר' יהודה אומר סימן בן י"ג שנה ויום אחד דברי הכל סימן

If a nine year old grows two hairs [in the pubic region] the growth should be attributed to a mole [and not as a sign of sexual maturity]. [If these hairs grow] from the age of nine years and one day until twelve years and one day, and they are still there [when the child reaches twelve, one opinion is that they should be attributed to a] mole, and Rabbi Yossi bar Rabbi Yehuda says they are a sign of sexual maturity. [If these hairs grow] when the child is thirteen years old and one day, then everyone agrees they are a sign of sexual maturity...(Kiddushin 16b)

Pre-Modern Descriptions of Puberty

The way in which children develop into adults has fascinated us for centuries. In fact, the earliest surviving statement on human growth dates back to the sixth century BCE, (not long after the prophet Jeremiah lived) and is by the Athenian poet Solon. One critic described his poem as combining "scientific sense with philosophical probability (if not, regrettably, with poetic elegance)." Here is Solon:

A young boy acquires his first ring of teeth as an infant and sheds them before he reaches the age of seven years. When the god brings to an end the next seven year period, the boy shows the signs of beginning puberty. In the third hebdomad, [ a period of seven years] the body enlarges, the chin becomes bearded and the bloom of the boy's complexion is lost. In the forth hebdomad physical strength is at its peak and is regarded as the criterion of manliness; in the fifth hebdomad a man should take thought of marriage and seek sons to succeed him. In the sixth hebdomad a man's mind is in all things disciplined by experience and he no longer feels the impulse to uncontrolled behavior. In the seventh he is at his prime in mind and tongue and also in the eighth, the two together making fourteen years. In the ninth hebdomad, though he still retains some strength, he is too feeble in mind and speech for the greatest excellence. If a man continues to the end of the tenth hebdomad, he has not encountered death before due time.

Hippocrates believed that puberty could be delayed in areas where "the wind is cold and the water is hard". Rabbi Shimon ben Gamliel (d. 70CE) would have agreed, because he thought that the growth of pubic hair was hastened in those who used the bathhouse regularly. But it is especially interesting to compare Aristotle's writings on puberty with those of the Talmud (which of course were codified several hundred years later).

In man, maturity is indicated by a change in the tone of the voice, by an increase in size and an alteration in appearance of the sexual organs, and also by an increase in size and alteration in appearance of breasts, and above in the hair growth above the pubes.

Aristotle (d. 322 BCE) seems to have put a lot of weight on the growth of pubic hair, just like the rabbis of in the Talmud did many years later. Galen, who died in 199 CE, was cautious about timing the onset of puberty: "Some begin puberty at once on the completion of the fourteenth year, but some begin a year or more after that" (De Sanitate Tuenda, or p288 of this translation). Jumping forward several centuries, we find that girls in Tuscany in 1428 were allowed to marry aged eleven and a half, although they were forbidden to live with their husbands until they were twelve. However the Bishop of Florence (later canonized as Saint Anthony) declared that cohabitation was allowed "provided the girl had reached puberty."

The Tanner Scale

Today, the stage of sexual maturity in children is most commonly measured using the Tanner scale, described by the British pediatrician James Tanner, who died in 2010. (He wrote a fascinating History of the Study of Human Growth as a sort of a hobby, but his day job was working as a Professor at the Institute of Child Health in London.) Here is how Tanner described his scale in boys, (from his original paper published in 1970):

Stage 1: Pre-adolescent. The velus [sic] over the pubes is no further developed than that over the abdominal wall, i.e. no pubic hair.

Stage 2: Sparse growth of long, slightly pigmented downy hair, straight or slightly curled, appearing chiefly at the base of the penis. This stage is difficult to see on photographs, particularly of fair-headed subjects...

Stage 3: Considerably darker, coarser, and more curled. The hair spreads sparsely over the junction of the pubes. This and subsequent stages were clearly recognizable on the photographs.

Stage 4: Hair is now adult in type, but the area covered by it is still considerably smaller than in most adults. There is no spread to the medial surface of the thighs.

Stage 5: Adult in quantity and type, distributed as an inverse triangle of the classically feminine pattern. Spread to the medial surface of the thighs but not up the linea alba or elsewhere above the base of the inverse triangle.

“There has been less discussion in the literature as to whether the appearance of pubic hair has advanced in females, although this does seem to be the case, pubarche having advanced by at least 6 months. The PROS study found stage II pubic hair to be apparent in African-American females at a mean age of 8·78 years and 10·51 years in whites.”

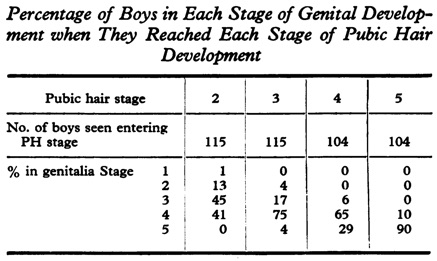

Tanner also described other signs of sexual maturity, since growth of pubic hair is not the only maker. In boys, for example, Tanner used a five-stage system for genital growth: in stage one, the "testes, scrotum, and penis are of about the same size and proportion as in early childhood," whereas in stage two, "the scrotum and testes have enlarged and there is a change in the texture of the scrotal skin..." Tanner noted that the stages of pubic hair development and the stages of genital development differ, so that a boy may reach full genital maturation sooner than he reaches stage five on the pubic hair scale.

From Marshall A. Tanner JM. Variations in the pattern of pubertal changes in boys. Archives of Disease in Childhood 1970. 45: 13-25.

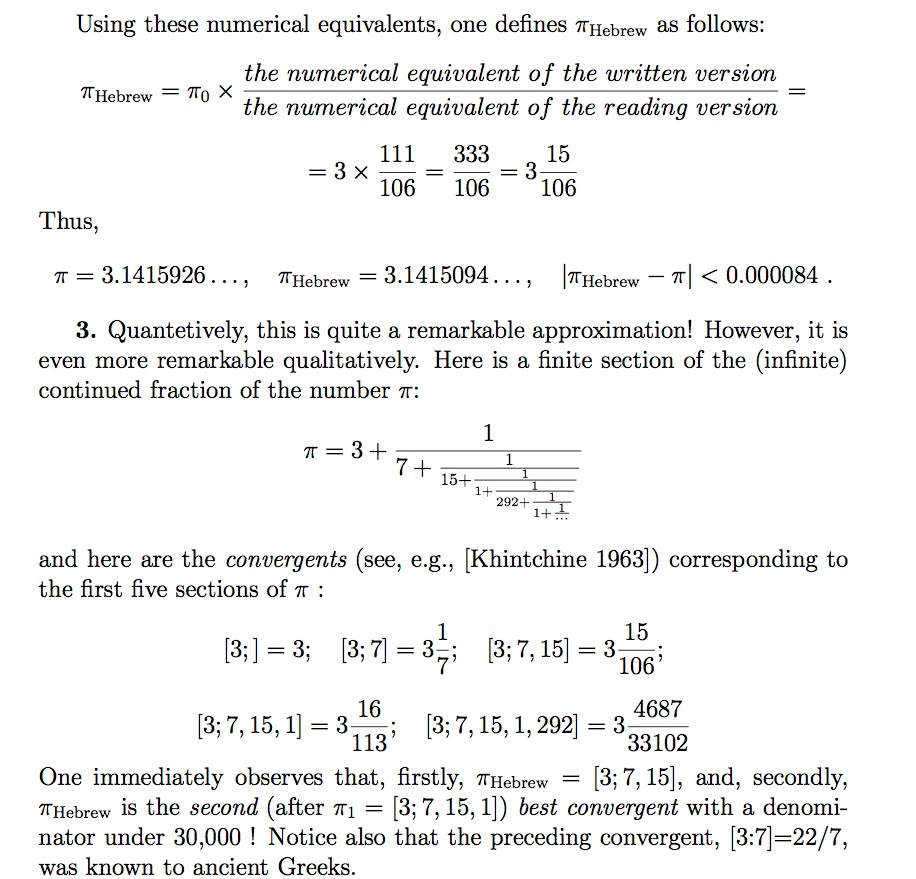

Tanner's work reveals what we already know intuitively. Maturity, whether sexual or emotional, is a process that takes time and proceeds through many stages. The rabbis of the Talmud relied predominantly on one marker of adulthood: sexual maturity as evidenced by a minimal of pubic hair growth. But they used it in conjunction with the age of the child. They also understood that the onset of these signs might be sooner in some children and later in others.

Sequence of events in puberty in girls (top) and boys. From Marshall A. Tanner JM. Variations in the pattern of pubertal changes in boys. Archives of Disease in Childhood 1970. 45:22.

In most European countries, the age of the onset of puberty (as measured by the onset of menstruation) has fallen by about a year per century. Boys also seem to be developing earlier than previously, possibly by more than a year. Data from the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) study of boys aged 8 –19 years, suggests that the mean age of onset of male genital development based on visual inspection is now about nine years for African-Americans and ten years for white boys.

Another First?

Last year we analyzed talmudic statements of R. Hiyya (who lived in the second half of the second century,) and Rava, (d. 350CE) who appear to have been the first to report an association between obesity and delayed puberty in boys. They claimed that puberty may be delayed in boys who are underweight, and this association has now been confirmed. As we noted then, none of the researchers has credited these talmudic sages for being the first to notice these associations. But Rava and R. Hiyya were first, and firsts count for something in science. The Baraita in today's daf may be the first recorded discussion of the lower limits of sexual maturity. But the rabbis of the Talmud used other markers of maturity, like breast development which is discussed in Masechet Niddah (47a).They distinguished between "lower" and "upper" signs of puberty, and so presaged the work of Tanner. (The rabbis also ruled that "all girls who are examined are examined by women". Thank heavens.)

There were several reasons why the Talmud had to codify the stages of physical maturity. Among these were to allow a father to decide to whom his daughter would marry.

A father who declares...my daughter is twelve years and a day is believed in order to marry the child off...(רמב׳ם הל׳ אישות ב:כג)

Today, any notion that a child under the age of twelve (or sixteen for that matter) would be mature enough to marry is utterly repugnant to us. But according to the UN in developing countries, one in every three girls is married before reaching the age of eighteen, and one in nine is married by the age of fifteen. When we read the Talmud we often get a glimpse into a Jewish world very different from our own. But some practices of that world still exist outside of the Jewish community today, to the shame of us all.

From United Nations Children’s Fund, Ending Child Marriage: Progress and prospects, UNICEF, New York, 2014.