בראשית 25:27

וַֽיִּגְדְּלוּ֙ הַנְּעָרִ֔ים וַיְהִ֣י עֵשָׂ֗ו אִ֛ישׁ יֹדֵ֥עַ צַ֖יִד אִ֣ישׁ שָׂדֶ֑ה וְיַעֲקֹב֙ אִ֣ישׁ תָּ֔ם יֹשֵׁ֖ב אֹהָלִֽים׃

And the boys grew: and ῾Esav was a cunning hunter, a man of the field; and Ya῾aqov was a plain man, dwelling in tents.

In explaining the meaning of the phrase “a man of the field” Rashi has no problem adopting a straightforward and non-midrashic approach:

איש שדה. כְּמַשְׁמָעוֹ, אָדָם בָּטֵל וְצוֹדֶה בְקַשְׁתּוֹ חַיּוֹת וְעוֹפוֹת

איש שדה A MAN OF THE FIELD — Explain it literally (i.e., not in a Midrashic manner): a man without regular occupation, hunting beasts and birds with his bow.

The Seforno (Obadiah ben Jacob Sforno, Italy, 1475–1549) followed Rashi’s example:

איש שדה. יודע בעבודת האדמה

איש שדה A MAN OF THE FIELD - He was skilled as a farmer

Esau hunted mysterious animals

But the Gaon of Vilna, Rabbi Elijah ben Solomon (1720-1797) thought this verse deserved a more fanciful explanation. And boy, he does not disappoint:

דברי אליהו תילדות

פרשת תולדות ויגדלו נערים ויהי עשו איש יודע ציד איש שדה הפי' של איש שדה י ל עד"ז דהכתוב סיפר שעשו היה יודע איך יצוד את איש השדה והוא אדני השדה הנזכר בכלאים פ ח מ׳ה והוא ידעוני הכתוב בתורה וצורתו צורת אדם בפרצוף וידים ורגלים והוא מחובר בטבורו בחבל גדול היוצא מן הארץ.

ואין כל בריה רשאה לקרב אליו במלא מדת החבל כי חוא הורג וטורף כל הקרב אליו.

וכשרוצים לצודו מורים בחצים בחבל עד שנפסק החבל וצועק בקול מר ומיד הוא מת ועשו היה יודע איך לצודו חיים ושיעור הכתוב הוא כאילו נכתב ויהי עשו איש יודע ציד לאיש שדה

The phrase “a cunning hunter, a man of the field” means the following: Esau was an excellent hunter who was able to hunt the creature known as the Ish Sadeh (איש שדה). This is the creature that rules over the fields (אדני השדה) that is mentioned in the Mishnah in Kila’im (8:5). This is also the creature known as the yidoni (ידעוני) in the Torah (Lev 19:31). Its face has the features of a person, as are his arms and legs, and it is attached from its umbilicus with what appears to be thick cord which comes from the earth.

No creature may venture close to it because it kills and maims all who approach it.

When it is hunted, they aim their arrows at the cord until it breaks. The creature then cries out and immediately dies. However, Esau was able to capture it alive, and the verse should be understood as if it were written “and Esau knew how to hunt the Ish Hasadeh (איש שדה).”

Incidentally, this is explanation is not original to the Gaon. It can be found, word for word, in the commentary of Rabbi Ovadiah of Bertinoro (c. 1445-1515) to the Mishnah (Kila’im 8:5). But it goes back as far at the thirteenth century, as we will see below.

The Yidoni was ….an orangutan

As the Gaon mentions, the yidoni that he posits was hunted by Esau is mentioned in the Torah, though its identity is uncertain. The Koren Bible thinks it is a wizard:

ויקרא יט, לא

אַל־תִּפְנ֤וּ אֶל־הָאֹבֹת֙ וְאֶל־הַיִּדְּעֹנִ֔ים אַל־תְּבַקְשׁ֖וּ לְטמְאָ֣ה בָהֶ֑ם אֲנִ֖י יְהֹ’ אֱלֹקיכֶֽם׃

You shall not apply to mediums or wizards, nor seek to be defiled by them: I am the Lord your God.

But let’s take a look at the commentary on the Mishnah of Rabbi Israel Lipschitz (1782–1860), known as the Tiferes Yisrael. In one of his commentaries called Yachin, he offers a precise identification of the yidoni:

נ"ל דר"ל וואלדמענש הנקרא אוראנגאוטאנג והוא מין קוף גדול בקומת וצורת אדם ממש

This is the “wild-man” known as an orangutan; it is a large monkey whose size and shape is exactly like that of a human.

And he continues:

רק שזרעותיו ארוכים ומגיעין עד ברכיו ומלמדין אותו לחטוב עצים ולשאוב מים וגם ללבוש בגדים כבן אדם ממש. ולהסב על השולחן ולאכול בכף ובסכין ובמזלג, ובזמנינו אינו מצוי רק ביערות גדולות שבאפריקא, אולם כפי הנראה היה מצוי גם בסביבות ארץ ישראל בהרי הלבנון

It has long arms that reach down to its knees. It can be trained to carry wood and draw water, and even to wear people’s clothing. It can sit at the table and eat with a spoon, knife and fork. Today, however, it is only found in large jungles in Africa, but it appears that it one could be found around Israel, in the forests of Lebanon.

Although he does not mention this fun fact, it turns out that the etymology of the word orangutan is from the Malay words orang, meaning "person", and hutan, meaning "forest.” This is, I think you will agree, awfully close to the meaning of איש שדה, no?

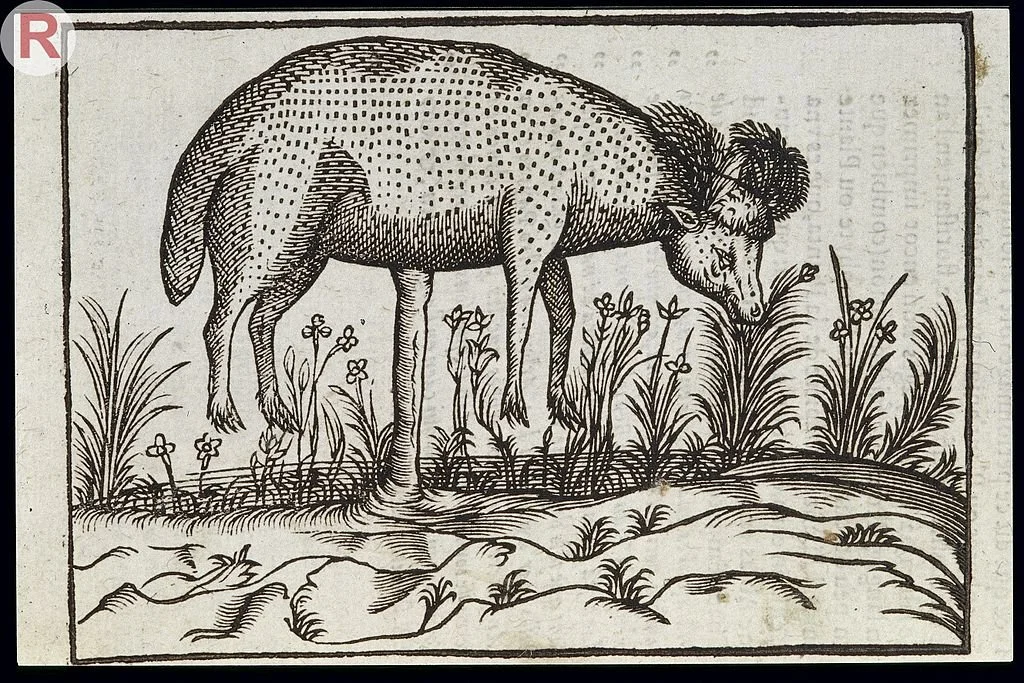

If this seems to be a bit of a cholent, it is. The description of the Ish Sadeh as being attached to the earth by some kind of umbilical cord invokes another legend, known as the Vegetable Lamb of Tartary, or alternatively, the Barometz. This was a mythical creature that was half-plant and half animal, usually in the form of a sheep. Like this:

From Duret, Claude (d.1611), Histoire admirable des plantes et herbes esmerueillables et miraculeuses en nature: mesmes d'aucunes qui sont vrays zoophytes, ou plant-animales. Paris : N. Bvon, 1605 Plate, p.330: 'Portrait du boramets de Scythie ou Tartarie'

Except instead of a lamb, think orangutan.

Rabbi Herman Adler Chief Rabbi, weighs in…

In 1887 Henry Lee published an entire book on the legend, called, appropriately enough The Vegetable Lamb of Tarty (London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle and Rivington, 1887). On pages 6–7, Lee describes his correspondence with Rabbi Hermann Adler, Chief Rabbi of the British Empire. Lee had heard that the legend is mentioned in the Jerusalem Talmud, but he could not find the citation and so he wrote to Rabbi Adler for some help. Here is the rabbi’s answer. Make of it what you will.

“It affords me much gratification to give you the information you desire on the Borametz. In the Mishna Kilaim, chap. viii. § 5 (a portion of the Talmud), the passage occurs:—‘Creatures called Adne Hasadeh (literally, “lords of the field”) are regarded as beasts.’ There is a variant reading,—Abne Hasadeh (stones of the field). A commentator, Rabbi Simeon, of Sens (died about 1235), writes as follows on this passage:—‘It is stated in the Jerusalem Talmud that this is a human being of the mountains: it lives by means of its navel: if its navel be cut it cannot live. I have heard in the name of Rabbi Meir, the son of Kallonymos of Speyer, that this is the animal called ‘Jeduah.’ This is the ‘Jedoui’ mentioned in Scripture (lit. wizard, Leviticus xix. 31); with its bones witchcraft is practised. A kind of large stem issues from a root in the earth on which this animal, called ‘Jadua,’ grows, just as gourds and melons. Only the ‘Jadua’ has, in all respects, a human shape, in face, body, hands, and feet. By its navel it is joined to the stem that issues from the root. No creature can approach within the tether of the stem, for it seizes and kills them. Within the tether of the stem it devours the herbage all around. When they want to capture it no man dares approach it, but they tear at the stem until it is ruptured, whereupon the animal dies.’ Another commentator, Rabbi Obadja of Berbinoro, gives the same explanation, only substituting—’They aim arrows at the stem until it is ruptured,’ &c. The author of an ancient Hebrew work, Maase Tobia (Venice, 1705), gives an interesting description of this animal. In Part IV. c. 10, page 786, he mentions the Borametz found in Great Tartary. He repeats the description of Rabbi Simeon, and adds what he has found in ‘A New Work on Geography,’ namely, that ‘the Africans (sic) in Great Tartary, in the province of Sambulala, are enriched by means of seeds like the seeds of gourds, only shorter in size, which grow and blossom like a stem to the navel of an animal which is called Borametz in their language, i.e. ‘lamb,’ on account of its resembling a lamb in all its limbs, from head to foot; its hoofs are cloven, its skin is soft, its wool is adapted for clothing, but it has no horns, only the hairs of its head, which grow, and are intertwined like horns. Its height is half a cubit and more. According to those who speak of this wondrous thing, its taste is like the flesh of fish, its blood as sweet as honey, and it lives as long as there is herbage within reach of the stem, from which it derives its life. If the herbage is destroyed or perishes, the animal also dies away. It has rest from all beasts and birds of prey, except the wolf, which seeks to destroy it.’ The author concludes by expressing his belief, that this account of the animal having the shape of a lamb is more likely to be true than that it is of human form.”

If you check the commentary of Rabbi Shimshon of Senz (c. 1150-1230) you will indeed find this explanation of the Mishnah in Kila’im:

ירושלמי (הל' ד') אמר רבי חמא ברבי עוקבא בשם רבי יוסי ברבי חנינא טעמא דרבי יוסי וכל אשר יגע על פני השדה (במדבר י״ט:ט״ז) בגדל מן השדה כלומר מין אדם הוא א"ר בר נש דטור הוא והוא חיי מטיבורא פסק טיבורא לא חיי ושמעתי בשם הר' מאיר ברבי קלונימוס מאשפירא שהיא חיה ששמה ידוע והיא ידעוני דקרא ומעצם שלה עושין כמין כשפים וכמין חבל גדול יוצא משורש שבארץ שבו גדל אותה החיה ששמה ידוע כעין אותם קישואין ודלועים אלא הידוע צורתו כצורת אדם בכל דבר בצורת פנים וגוף וידים ורגלים ומטיבורו מחובר לחבל היוצא מן השורש ואין כל בריה רשאי ליקרב כמלא החבל שטורפת והורגת כמלא החבל ורועה כל סביבותיה וכשבאין לצודה אין אדם רשאי לקרב אצלה אלא גוררין אותה אל החבל עד שהוא נפסק והיא מיד מתה:

Rabbi Shimshon credited the legend to “Meir, the son of Kallonymous of Speyer” whose identity I am still figuring out. But this appears to be the earliest Hebrew source for the myth of the Ish Sadeh as the Barometz, (or something like it).

So to recap:

Here is what we have discovered:

There was a legend about a half-plant-half animal that appears to begin around the 11th century with a Rabbi Meir, who perhaps lived before 1196, perhaps in Speyer. Rabbi Shimshon of Sens passed the legend down, and it travelled from Ashkenaz to Italy where it appears in the writings of the Seforno. It then appears in some form in Ma’aseh Tuvia published in 1707, and then finds its way to the Gaon of Vilna, who sort of mixed it together with the Ish Sadeh, from where, perhaps, the Tiferet Yisrael got his explanation of an orangutan (but not a Boramtez). I am sure there are others along the way, but it is time to stop. There are tehilim that must be said for our brothers and sisters in Israel.

אַחֵינוּ כָּל בֵּית יִשְׂרָאֵל

הַנְּתוּנִים בַּצָּרָה וּבַשִּׁבְיָה

הָעוֹמְדִים בֵּין בַּיָּם וּבֵין בַּיַּבָּשָׁה

הַמָּקוֹם יְרַחֵם עֲלֵיהֶם

וְיוֹצִיאֵם מִצָּרָה לִרְוָחָה

וּמֵאֲפֵלָה לְאוֹרָה

וּמִשִּׁעְבּוּד לִגְאֻלָּה

הָשָׁתָא בַּעֲגָלָא וּבִזְמַן קָרִיב