בראשית 41:1

וַיְהִ֕י מִקֵּ֖ץ שְׁנָתַ֣יִם יָמִ֑ים וּפַרְעֹ֣ה חֹלֵ֔ם וְהִנֵּ֖ה עֹמֵ֥ד עַל־הַיְאֹֽר׃

And it came to pass at the end of two years, that Pharoh dreamed: and, behold, he stood by the River.

Dreams feature a great deal in the story of Joseph and his brothers. Joseph shares his dreams with his brothers, which was not a good idea. As a result, he ends up in a prison in Egypt, where he accurately interprets two sets of dreams, Consequently is brought to Pharoh he ends up interpreting Pharoh’s famous seven-fat-cow-seven-ears-of-corn dreams. That’s three sets of dreams all in a few chapters. But why, exactly, do we dream? Let’s start with the the Talmud,

Dreams in the Talmud

גיטין נב, א

אמר, דברי חלומות לא מעלין ולא מורידין

Rabbi Meir used to say: The content of dreams is inconsequential (Gittin 52a)

The Talmud contains many theories about the content of dreams. In Berachot (10b) Rabbi Hanan taught that even if a dream appears to predict one's imminent death, the one who dreamed should pray for mercy. R. Hanan believed that dreams may contain a glimpse of the future, but that prayer is powerful enough to changes one's fate. Later in Berachot (55b), R. Yohanan suggested a different response to a distressing dream: let the dreamer find three people who will suggest that in fact the dream was a good one (a suggestion that is codified in שולחן ערוך יורה דעה 220:1).

He should say to them "I saw a good dream" and they should say to him "it is good and let it be good, and may God make it good. May heaven decree on you seven times that it will be good, and it will be good.

Shmuel, the Babylonian physician who died around 250 CE, had a unique approach to addressing the content of his own dreams. "When he had a bad dream, he would cite the verse 'And dreams speak falsely' [Zech. 10:2]. When he had a good dream he would say "are dreams false? Isn't it stated in the Torah [Numbers 12:6] 'I speak with him in a dream'?" (Berachot 55b). In contrast, Rabbi Yonatan suggests that dreams do not predict the future: rather they reflect the subconscious (Freud would have been proud). "R. Yonatan said: a person is only shown in his dreams what he is thinking about in his heart..." (Berachot 55b). And from today's page of Talmud, we learn that Rabbi Meir believed dreams were of no consequence whatsoever.

“It is of interest that two millennia separated the first detailed description of the major peripheral characteristics of dreaming from the first contemporary experimental results of brain research in this field, while only about 60 years were necessary to establish relatively solid knowledge of the basic and higher integrated neurobiological processes underlying REM sleep.”

What does Science have to Say?

Dreaming takes place during the REM (Rapid Eye Movement) stage of sleep, when there is brain activation similar to that found in waking, but muscle tone is inhibited and the eyes move rapidly. This type of sleep was only discovered in the 1950s, and since then it has been demonstrated in mammals and birds (but not yet in robots). Most adults have four or five periods of REM sleep per night, which mostly occur in 90 minute cycles. Individual REM periods may last from a few minutes to over an hour, with REM periods becoming longer the later it is in the night.

Here are some theories about why we dream, all taken from this paper. (The author, J. Allan Hobson, directed the Laboratory of Neurophysiology at the Massachusetts Mental Health Center from 1968 to 2003. He also published more than 200 peer-reviewed articles and 10 books on sleep and dreaming. So he knows something about the physiology of sleep.)

1. Sleep and dreaming are needed to regulate energy

Deprive a lab rat of all sleep and it will die. Deprive a lab rat of REM sleep so that it does not dream, and it too will die. These sleep-and-dream deprived rats lost weight and showed heat seeking behavior. This suggests for animals which regulate their body temperature, sleep is needed to control both body temperature and weight. Importantly, only mammals and birds are homeothermic, and they are also the only animals which are known to have REM sleep.

2. Sleep deprivation and psychological equilibrium

Based on a number of experiments in healthy human volunteers, it has been shown that sleep and dreaming are essential to mental health. "The fact that sleep deprivation invariably causes psychological dysfunction" wrote Prof. Hobson in his review, "supports the functional theory that the integrity of waking consciousness depends on the integrity of dream consciousness and that of the brain mechanisms of REM sleep." (When we studied Nedarim 15 we noted however, that eleven days of sleep deprivation seemed to have no ill effects in one man.) The relationship between dreaming and psychological health is rather more complicated though: monamine-oxidase inhibitors completely repress REM sleep, and yet are an effective class of anti-depressants. There appears to be a relationship between dreaming and psychological well being, but its parameters require much more study.

3. Sleep, Dreams and Learning

In 1966, it was first suggested that REM sleep is related to the brain organizing itself. This suggestion was later supported by studies which showed that the ability of an animal to learn a new task is diminished their REM sleep is interrupted. Other studies show that REM sleep in humans is increased following an intensive learning period.

“...dreaming could represent a set of foreordained scripts or scenarios for the organization of our waking experience. According to this hypothesis, our brains are as much creative artists as they are copy editors.”

Nightmares and Fasting

We've all had dreams that frighten or upset us. The major code of Jewish law take bad dreams seriously. While fasting is absolutely forbidden on Shabbat, it is permitted in two instances: when Yom Kippur falls on Shabbat and when you've had a bad dream and need to undertake a fast "to tear up the heavenly decree." Here is the ruling:

שולחן ערוך אורח חיים הלכות שבת סימן רפח

סעיף ד

מותר להתענות בו תענית חלום כדי שיקרע גזר דינו. וצריך להתענות ביום ראשון, כדי שיתכפר לו מה שביטל עונג שבת

It is permitted to fast on Shabbat because of a bad dream, in order for the bad ruling to be torn up. However he must then also fast on Sunday, in order to atone for the fact that he ruined his Shabbat enjoyment by fasting...

There are several psychological definitions of a nightmare. One describes nightmares, as "characterized by awakenings primarily from REM sleep with clear recall of disturbing mentation." These bad dreams are common, occurring in 2-6% of the population at least once a week. They seem to be more prevalent in children and less prevalent in the elderly, but in all age groups women report having nightmares more often than men. Nightmares are also more frequent in patients with psychiatric disorders such as anxiety, neuroticism, schizophrenia, sociality and post traumatic stress disorder. And in all populations they are more frequently reported during episodes of stress.

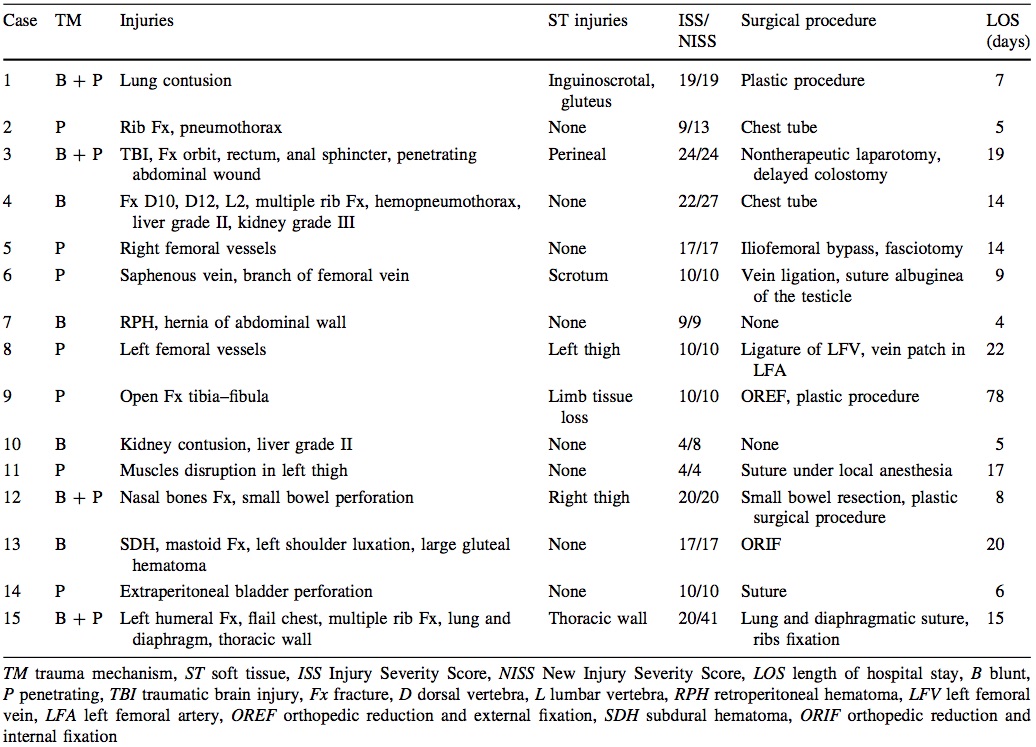

There are a number of psycho-analytical models of nightmare formation, but little empirical evidence to support any of them. They are shown in the table below.

| Psychoanalytic and neo-psychoanalytic models of nightmare formation | |

|---|---|

| Authors | Core mechanism producing nightmares |

| Freud 1900 | Transformation of libidinal urges into anxiety that punishes the self (masochism); analogous to the neurotic anxiety underlying phobias |

| Jones 1951 | Expression of repressed, exclusively incestuous, impulses |

| Jung 1909-1945 |

Residues of unresolved psychological conflicts.Individuation or development of the personality |

| Fisher et al. 1970 | Attempts to assimilate or control repressed anxiety stemming from past or present conflicts |

| Greenberg 1972 | Failure in dream function of mastering traumatic experience |

| Lansky 1995 | Transformation of shame into fear (post-traumatic nightmares only) |

| Solms 1997 | Epileptiform (seizure) activity in the limbic system (recurring nightmares only). Activation of dopaminergic appetitive circuits in mediobasal forebrain and hallucinatory representation by occipito-temporal-parietal mechanisms (nonrecurring nightmares and normal dreaming) |

| From Nielsen T and Levin, R. Nightmares: A new neurocognitive mode. Sleep Medicine Reviews 2007:11 (4); 295-310. | |

A review paper from researchers in Montreal and Yeshiva University summarizes the research in this way:

In sum, although clinical and, to some extent, empirical evidence supports different psychoanalytic models of nightmare formation, for the most part such models have not been subjected to rigorous empirical scrutiny. Rather, their central tenets have been integrated with more recent nightmare models, where empirical evidence is less scarce.

These same researchers suggest that nightmares "result from dysfunction in a network of affective processes that, during normal dreaming, serves the adaptive function of fear memory extinction." Fear memory occurs when an innocuous stimulus (like a door bell ringing) is paired with an unpleasant experience (like an electric shock). Fear memory may be useful if it saves the individual from repeating a dangerous error. Extinction memories override the original fear memories and allow the individual to hear that ringing door bell without fearing an electric shock. The suggestion is that nightmares occur when the brain does not properly process fear extinction memories, For this reason nightmares are more prevalent in those with stress or psychiatric disorders. It's an interesting theory, but one that has not yet gathered much empirical evidence for its support. But there is no doubting the relationship between psychiatric disorders, stress, and nightmares, and we noted earlier that R. Yonatan claimed "a person is only shown in his dreams what he is thinking about in his heart..." (Berachot 55b). Perhaps this is why it is permitted to fast on Shabbat after a nightmare.

Interestingly the Shulchan Aruch records an opinion that such Shabbat fasting is not permitted for a nightmare that appears only once; rather it is only allowed if it appears three times or more ( י"א שאין להתענות תענית חלום בשבת אלא על חלום שראהו תלת זימני). This is now more readily understood in light of the relationships we have noted between nightmares and psychological wellbeing; a recurrent nightmare may be associated with a more deeply felt stressful situation, and so it is only these recurrent bad dreams that allow for a Shabbat fast. One-off nightmares are not reflective of this stress, and so fasting on their account is not permitted on Shabbat.

| The Realism and Bizarreness of 365 Dreams | |

|---|---|

| Category | Frequency (%) |

| Possible in waking life, everyday experiences | 29 |

| Possible in waking life, uncommon elements | 50 |

| One or two bizarre or impossible elements | 27 |

| Several bizarre elements | 4 |

| From M. Schredl, et al. Dream content and personality. Dreaming 1999. (9): 257–263 | |

In Summary

At best, we can say that contemporary science has a poor understanding of why we dream. Hobson concludes his review stating that dreaming is "the subjective experience of a brain state with phenomenological similarities to - and differences from - waking consciousness, which is itself associated with a distinctive brain state." Well thanks for that Professor. But not very helpful.

Dreams are very important to how we function as humans but we seem to have no idea how dreams serve to keep us from dying or getting very sick. That we must dream in order to function seems to be certain; but why we dream about what we do is far less known. And don't trust every scientific paper you read on the subject. Publication and peer review is no guarantee of veracity. Let's end with a good example of scientific nonsense from this paper published in the journal Sleep and Hypnosis, which seeks to explain why some dreams portend the future. (Well, um, actually they don't. But do go on.) Just its title alone should make you run for the hills: Dreams, Time Distortion and the Experience of Future Events: A Relativistic, Neuroquantal Perspective. And it only gets better:

“If dreams and related altered states are actually the experiences of biophotons within the brain...then the temporal discrepancies between precognitive experiences and subsequent verified events may reflect the relativistic and quantum properties of minute differential velocities in electromagnetic phenomena. The average discrepancy of about two to three days between the experience and the event in actual cases supported this hypothesis.

The moderately strong correlation between the global geomagnetic activity at the time of precognitive experiences, primarily during dreams, and the geomagnetic activity during the two days before the event in those cases where the discrepancy is more than 6 days suggests a variant of entanglement between photons emitted during the event and those experienced before the event. The marked congruence of gravitational waves, geomagnetic activity, the Schumann resonance and the peak power of brain activity during different states, particularly when the sensitivity of the right hemisphere is considered, indicates a physical substrate by which prescience could occur.”

Rabbi Meir, the great sage of the Talmud, believed that the content of dreams was of no consequence whatsoever. He may well said that same about some of the contemporary scientific explanations of dreaming.

“אמרו לו בחלום מעשר שני של אביך שאתה מבקש הרי הוא במקום פלוני, אף ע”פ שמצא שם מה שנאמר לו אינו מעשר, דברי חלומות לא מעלין ולא מורידין

If a man was told in a dream that Ma’aser Sheni [a tithe on produce] belonging to his father was to be found in a certain location, even if he found some produce in that same location, it is not to be considered set aside for this tithe. For the content of dreams is of no consequence.”