From here.

מנחות מב, ב

אמר ליה אביי לרב שמואל בר רב יהודה הא תכילתא היכי צבעיתו לה אמר ליה מייתינן דם חלזון וסמנין ורמינן להו ביורה [ומרתחינן ליה] ושקלינא פורתא בביעתא וטעמינן להו באודרא ושדינן ליה לההוא ביעתא וקלינן ליה לאודרא

Abaye said to Rav Shmuel bar Rav Yehuda: How do you dye this sky-blue wool to be used for ritual fringes? Rav Shmuel bar Rav Yehuda said to Abaye: We bring blood of a chilazon and various herbs and put them in a pot and boil them. And then we take a bit of the resulting dye in an egg shell and test it by using it to dye a wad of wool to see if it has attained the desired hue. And then we throw away that egg shell and its contents and burn the wad of wool.

It is clear from Rav Shmuel's detailed instructions that the entire process depends on one ingredient - "the blood of the chilazon" - which was used to make the dye that produced techelet and color the ritual fringes known as tzitzit. But what exactly is the chilazon? It turns out to be a rather common snail found in the Mediterranean, but for centuries the identity of the chilazon was lost. Here is the story of how it was re-discovered.

Pliny the Elder and his recipe

It wasn't just the Jews that were boiling up blue dye. Pliny the Elder (23-79 CE.) lived at least two centuries before Abaye and Rav Shmuel, and left us his own version of the process outlined in today's page of Talmud:

The most favourable season for taking these fish is after the rising of the Dog-star, or else before spring... After it is taken, the vein is extracted...to which it is requisite to add salt, a sextarius [~20oz] to every hundred pounds of juice...leave them to steep for a period of three days...then set to boil in vessels of tin... About the tenth day, generally, the whole contents of the cauldron are in a liquified state, upon which a fleece...is plunged into it by way of making trial...The wool is left to lie in soak for five hours, and then, after carding it, it is thrown in again, until it has fully imbibed the colour... To produce the Tyrian hue the wool is soaked in the juice of the pelagiæ while the mixture is in an uncooked and raw state; after which its tint is changed by being dipped in the juice of the buccinum [a sea snail]. It is considered of the best quality when it has exactly the colour of clotted blood, and is of a blackish hue to the sight, but of a shining appearance when held up to the light; hence it is that we find Homer speaking of "purple blood".

So Pliny described a “fish” as the source of the dye. Was this the sea creature called the chilazon? Later in this tractate, (44a) we have another description of the mysterious chilazon.

ת"ר חלזון זהו גופו דומה לים וברייתו דומה לדג ועולה אחד לשבעים שנה ובדמו צובעין תכלת לפיכך דמיו יקרים

The Sages taught: This chilazon, [which is the source of the sky-blue dye used in ritual fringes, has the following characteristics:] Its body resembles the sea, its form resembles that of a fish, it emerges once in seventy years, and with its blood one dyes wool sky-blue for ritual fringes. It is scarce, and therefore it is expensive.

It is sea-like and fish-like and is rare ("once in seventy years"), and it is hard to find. OK, but not terribly helpful in figuring out its identity.

As early as 2,000 BCE the Phoenicians had been producing a blue-purple dye from shellfish. The identity of this chilazon creature was clear to the Romans and to sages of the Talmud, but it was lost over the centuries. Or almost lost. It was a point of scholarly and religious debate in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and then some neighbors of mine when I lived in Eftat figured it out.

“As early as 2,000BCE purple dye was associated with the Phoenicians, who traded in purple-dyed fabrics...The word “Canaan” may derive from the Akkadian kinahhu, “red-purple,” while “phoenicia” probably comes from the Greek phoinos, “dark-red”...the shellfish utilized for these dyes are the Murex trunculus and the Murex brandaris. The shellfish were crushed, boiled in salt, and placed in the sun; afterwards the secretions turned purple. Eight thousand mollusks yielded one gram of purple dye.”

Identifying the Chilazon

1. The Rebbe of Radzyn

The tradition of using a sea creature to dye clothing was never entirely lost. In 1685, for example, a Mr William Cole of Bristol reported that a "purple-fish" (by which he meant a sea snail or mollusk) was being used to dye "fine linens of ladies and gentlemen" on the coast of Ireland. But it wasn't until the nineteenth century that the search was taken seriously by the Jewish community.

“...there was a certain person living by the Sea-side in some Port or Creek in Ireland, who made considerable gain by marking with a delicate durable Crimson Color, fine Linnen of Ladies, Gent &c...made by some liquid substance taken out of a Shell-fish...”

The common cuttlefish - the source of the Radzyn techelet. Courtesy of the Monterey Bay Aquarium.

It was R. Gershon Henoch Leiner, the Rebbe of Radzyn(1839-1890) who began the modern search for the clilazon. Once the creature had been identified he argued, it would be used dye the strings of the otherwise white tzitzit, and return to a more authentic observance of the mitzvah. The search brought the rebbe to Naples, Italy, where he concluded that the cuttlefish (sepia officinalis), a kind of squid, was the long-lost chilazon. The cuttlefish produced a dark ink when threatened, and after some help from local chemists, he hit on a method to turn that ink into a blue dye.

However, there were three problems with the Radzyn techelet. First, Maimonides in his Mishnah Torah ruled that techelet must resist fading, but the Radzyn dye could be easily washed out.

“וְהַתְּכֵלֶת הָאֲמוּרָה בַּצִּיצִית צָרִיךְ שֶׁתִּהְיֶה צְבִיעָתָהּ צְבִיעָה יְדוּעָה שֶׁעוֹמֶדֶת בְּיָפְיָהּ וְלֹא תִּשְׁתַּנֶּה

The blue thread mentioned in connection with fringes must be dyed with a special dye which retains its color and does not change...”

Second, in order to produce Radzyn techelet, the cuttlefish needed to be killed to extract its ink. But the Talmud (Shabbat 75a) notes that the longer the chilazon is alive, the better its dye (דכמה דאית ביה נשמה טפי ניחא ליה כי היכי דליציל ציבעיה). And the third problem with the Radzyn-cuttlefish-is-techelt theory was Rabbi Isaac Halevi Herzog.

2. Rabbi Isaac Halevi Herzog

The Banded Dye-Murex, Murex trunculus. From here.

Rabbi Isaac Halevi Herzog (1888-1959) was born in Poland and at the age of ten emigrated with his family to Leeds in the north of England. There he was educated in talmudic studies mostly by his father, and he later attended the University of London There, the topic of his PhD thesis was "The Dying of Purple in Ancient Israel" and focused on the identity of the chilazon. R. Herzog went on to succeeded Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook as the Ashkenazi Chief Rabbi of Palestine, a position he held from 1936-1948.

R. Herzog was critical of the conclusion of the Rebbe of Radzyn that identified the common cuttlefish as the chilazon. In 1909 he had the Radzyn dye sent to the accomplished German chemist Paul Friedlander, who had earlier identified (or re-identified) the murex trunculus as the source of the dye called Tyrian purple (a discovery for which Friedlander was awarded the Lieben Prize in Chemistry). Friedlander tested the Radzyn dye and concluded it was itself unable to produce the blue color of techelet. Others chemists concluded that the Radzyn dye was in fact a synthetic compound known as Prussian blue, produced by the oxidation of ferrous ferrocyanide salts. This was confirmed when R. Herzog obtained the recipe for the dye from Radzyn hasidim. It called for the cuttlefish dye to be heated with iron filings and potash, and these hasidic dyers were actually making Prussian blue. In fact the color of the Radzyn dye was nothing to do with the cuttlefish - it all came from the added chemicals. This left R. Herzog with a problem: if the cuttlefish was not in fact the chilazon, well then what was?

Although it was known that the murex could produce a purple-blue dye, R. Herzog rejected this for the following reasons:

1. The snail does not appear "once every seventy years" yet this description appears in the Talmud (on 44a).

2. The dye is not color fast. Or at least that is what he thought.

3. The dye is a purple-blue color. But techelet is sky blue, as the great Rabbi Meir reminds us:

סוטה יז, א

היה ר"מ אומר מה נשתנה תכלת מכל מיני צבעונין מפני שהתכלת דומה לים וים דומה לרקיע ורקיע דומה לכסא הכבוד

R. Meir used to explain how techelt is different from all other colors: The color of techelet is similar to the color of the ocean; and the color of the ocean is similar to the color of the sky; and the color of the sky is similar to God's Glorious Throne.

Poor Rabbi Herzog never did reach a conclusion about the identity of the chilazon. But he was certain of two things. The Radzyn dye was not techelet, and the Radzyn cuttlefish was not the chilazon. Something was missing. And that something was sunlight.

It is all about the sunlight. From Ptil Tekhelet.

The dye produced from the murex snails is indeed dark purple and not permanent, but (and this is super important) if it was exposed to bright sunshine it turned a magnificent sky-blue color, and it didn't fade or wash out. This was discovered quite by accident in the early 1980s by Dr. Otto Elsner of the Shenkar Institute in Tel Aviv. Chemists who had produced the purple dye from the murex snail had done so in their labs, far away from natural sunshine. But the dye extracted from the gland of the murex snail, when exposed to sunlight, turns blue in color. Bingo. Sky-blue techelet.

“Elsner researched the chemical process taking place in his sun-drenched dye mixture and discovered that while in solution the dye molecules are less stable than in their natural condition. Ultraviolet energy - such as found in the rays of bright sunlight - can break the bonds that attach some of the atoms to each other within the dye molecule. These photochemical processes alter the purple and red constituents of the murex extract and leave primarily indigo, which is of course, pure sky blue.”

3. my neighbors in efrat.

In the late 1990s I lived in Efrat, part of the Gush Etzion Block, and was a neighbor of Baruch and Judy Sterman. It was their hard work, together with Ari Greenspan, Joel Guberman, and many others, who helped restore the ancient tradition of techelet. While the ability of the murex to produce the dye was already known, and the need for ultraviolet light to fix the dye had been fortuitously discovered, this group perfected the harvesting of the snails, (which involved, I kid you not, Greek and later Croatian fishermen) and set about manufacturing techelt-dyed tzitzit on a large scale. To date their organization Ptil Tekhelet have produced some 200,000 pairs, as well as this excellent guide to the process for those who are learning this passage in the Daf Yomi cycle. For a deep dive into all things techelet, I also recommend their fascinating book “The Rarest Blue.”

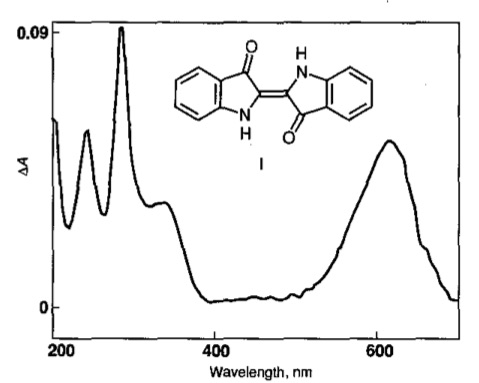

The ABSORPTION Spectrum of Murex Techelet

In 1991, Wouters and Verhecken published High-performance liquid chromatography of blue and purple indigoid natural dyes in the rather niche Journal of the Society of Dyers and Colourists. The two Belgium chemists measured the absorption spectra of various indigo containing dyes including “silk fabric, stained with the contents of the hypobranchial gland of Murex trunculus.” The absorption spectrum measures the wavelength of radiation (or light) absorbed by an object, and it is this absorption that gives objects their color. Here is the absorption spectrum of indigotin, the color-giving component of techelet:

Absorption spectrum in the u.v. and visible light region of Indigotin. From JWouters and A Verhecken. High-performance liquid chromatography of blue and purple indigoid natural dyes. JSDC 1991: 107; 266-269.

As you can see there is a peak around 613nm. A similar finding was reported in 2015 by a researchers from the Israel Antiquities Authority and Bar-Ilan University, when they examined textiles found in a cave in Wadi Murabba'at, the Judean desert. The textiles date to the Roman period, were identified as having been dyed with using the murex sea snail Hexaplex trunculus. Here is the absorption spectrum they published:

UV–visible spectra of the compounds found in Murex species: indigotin (IND) and its derivatives, monobromoindigotin (MBI) and dibromoindigotin (DBI), with absorbance maxima between 601 nm and 613 nm; indirubin (INR), monobromoindirubin (MBIR), and dibromoindirubin (DBIR) with absorbance maxima between 536 nm and 544 nm. From Sukenik et al. Chemical analysis of Murex-dyed textiles from wadi Murabba'at, Israel. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports. 2015; 3:565–570.

It too reports that indigotin (and its derivatives) have absorbance maxima between 601nm and 613 nm.” The number 613 of course has a special significance in Judaism; it is the traditional number of commandments that Jews must observe. This coincidence was noted by the Ptil Tekhelet organization who note it in their guide to Menachot chapter 4:

Now in fact, as you can tell from the figures above, the peak absorption spectrum of indigotin is not 613nm, but in the 200-300nm range. However this peak lies in the ultraviolet part of the spectrum, and so is not visible to us (though bees are able to see it). Make of this finding what you will.

A do-it-yourself guide to making techelet

This week I carried out a very unscientific survey of the number of techelt colored tzitizit worn in my shul. Out of a total of 58 talesim, 7 (12%) had techelet fringes (and I saw no techelet fringes in the women’s section). So if you want to get a set for yourself, you can either buy a ready-made pair, or do-it-yourself and follow this recipe (courtesy of Baruach Sterman).

Find the snails, break them open and extract the glands

Mush those glands in a food processor (they take on a dark purple hue), and then dry them out (at this point they are very stable and can be stored for a long time - even years - without refrigeration).

When ready to dye, put the dye into solution and produce a chemical process called reduction. To do that add water and a base and a reducing agent (Baruch uses sodium dithionite) and heat moderately. (In ancient times this was done by a two-week fermentation process which has been replicated).

Once the dye is in solution it takes on a green-yellow color (this is called leuco-indigo) and at that point expose to sunlight. Then immerse the wool/threads.

When the wool is removed and exposed to air, the dye undergoes oxidation and takes on its final color - and becomes insoluble again which keeps it fixed in the wool matrix.

That’s all there is to it. So what are you waiting for?