נדרים כ, א

תניא "בעבור תהיה יראתו על פניכם" זו בושה "לבלתי תחטאו" מלמד שהבושה מביאה לידי יראת חטא מיכן אמרו סימן יפה באדם שהוא ביישן. אחרים אומרים כל אדם המתבייש לא במהרה הוא חוטא, ומי שאין לו בושת פנים בידוע שלא עמדו אבותיו על הר סיני

It was taught in a Baraisa: "So that the awe of Him will be on your faces" (Ex. 20:17). This refers to the characteristic of being susceptible to shame [since bushing is that which is noted "on your faces". The verse continues] "So that you will not sin". This teaches that shame leads to the fear of sin. From this [teaching] they said it is a good sign for a person to be [easily] embarrassed. Others said that any person who feels embarrassed will not quickly sin. And if a person is not [the kind of person who is] embarrassed - it is known that his ancestors did not stand and Mount Sinai.

Detail from A Girl with a Black Mask by Pietro Antonio Rotari

Charles Darwin called blushing "the most peculiar and the most human of all expressions." It occurs when the face, ears, neck and upper chest redden on darken in response to perceived social scrutiny or evaluation. It is this feature of blushing - that it is seen on a person's face, that leads the Baraisa on this daf to understand the verse "So that the awe of Him will be on your faces"as referring to blushing. And as the commentary of the Ran explains, it is because blushing is so easily seen by others, that is serves to prevent a person from sinning:

מלמד שהבושה מביאה לידי יראת חטא, דעל פניכם משמע בושת פנים, וכתיב בתריה לבלתי תחטאו

WHEN DO WE BLUSH?

There appear to be four social triggers that result in blushing: a) a threat to public identity; 2) praise or public attention 3) scrutiny, and oddly enough, 4) accusations of blushing. This last trigger is especially fascinating: just telling a person that they are blushing - even when they are not - can trigger a blush.

Blushing is not only triggered by certain social situations; it also triggers other responses in those who blush. The most commonly associated behaviors are averting the gaze and smiling. Although gaze aversion is a universal feature of embarrassment, its frequency differs across cultures: in the United kingdom 41% report averting their eyes when they are embarrassed, whereas only 8% of Italians report doing so. Smiling is also a common response. Up to a third of those who are embarrassed display a "nervous" or "silly grin."

“The blush is ubiquitous yet scarcely understood. In the past it has attracted little scientific attention and it is only in recent years that it has begun to attract systematic scientific attention.”

WHY DO WE BLUSH?

It is unclear why humans blush. Of course, we blush when we are embarrassed, but why should this physiological response occur? The blood vessels in the face (and the other areas that blush) seem to differ structurally from other vessels, and so respond in a unique way. But just how they do so, and why, remains a physiological mystery. Here's the surgeon Atul Gawande's explanation, from the pages of The New Yorker.

Why we have such a reflex is perplexing. One theory is that the blush exists to show embarrassment, just as the smile exists to show happiness. This would explain why the reaction appears only in the visible regions of the body (the face, the neck, and the upper chest). But then why do dark-skinned people blush? Surveys find that nearly everyone blushes, regardless of skin color, despite the fact that in many people it is nearly invisible. And you don’t need to turn red in order for people to recognize that you’re embarrassed. Studies show that people detect embarrassment before you blush. Apparently, blushing takes between fifteen and twenty seconds to reach its peak, yet most people need less than five seconds to recognize that someone is embarrassed—they pick it up from the almost immediate shift in gaze, usually down and to the left, or from the sheepish, self-conscious grin that follows a half second to a second later. So there’s reason to doubt that the purpose of blushing is entirely expressive.

There is, however, an alternative view held by a growing number of scientists. The effect of intensifying embarrassment may not be incidental; perhaps that is what blushing is for. The notion isn’t as absurd as it sounds. People may hate being embarrassed and strive not to show it when they are, but embarrassment serves an important good. For, unlike sadness or anger or even love, it is fundamentally a moral emotion. Arising from sensitivity to what others think, embarrassment provides painful notice that one has crossed certain bounds while at the same time providing others with a kind of apology. It keeps us in good standing in the world. And if blushing serves to heighten such sensitivity this may be to one’s ultimate advantage.

BLUSHING AND CROSSING BOUNDARIES

So blushing may confer an advantage. It keeps us in good social standing, insuring that we do not step outside of the bounds of accepted behavior. This notion is supported by some recent work (published more than a decade after Gawande's 2001 article) that supports this notion of blushing having a social utility. Those who blush frequently showed a positive association between blushing and shame. These frequent blushers generally behaved less dominantly and more submissively. Writing in the journal Emotion in 2011 (yes, that really is the name of this academic journal), three Dutch psychologists demonstrated that blushing after a social transgression serves a remedial function. In their (highly experimental lab) work on human volunteers, blushers were judged more positively and were perceived as more trustworthy than their non-blushing counterparts.

But Not All Shame is Useful

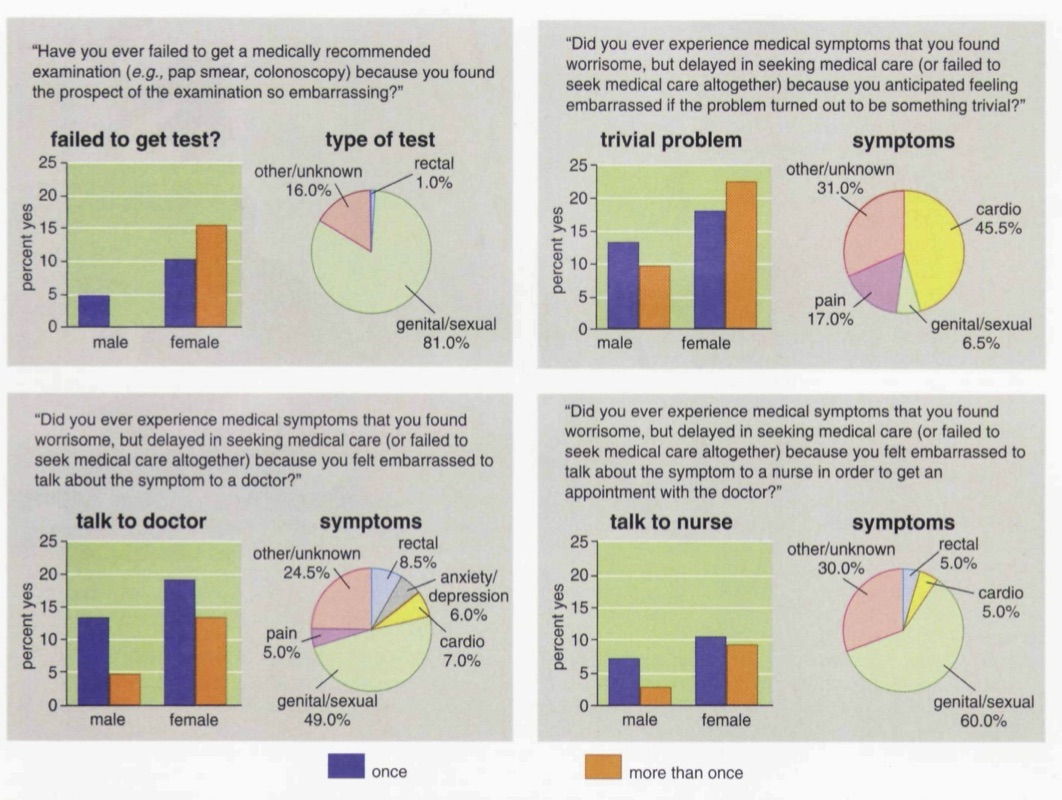

While there are useful features of shame, it also has negative effects. Perhaps the best documented of these is shame as a cause for delay in many types of medically recommended examinations that involve the parts of the body usually kept private. Interestingly, other types of shame that are an impediment to timely medical testing is the shame that the symptom might turn out to be from a "trivial cause" (though in my many years serving in the emergency department, I recall no patients exhibiting this kind of embarrassment).

Negative consequences of fear of embarrassment on health. From Harris. Embarrassment: A Form of Social Pain. American Scientist 2006. 94; 524-533.

Do Monkeys Feel Shame?

In a 2006 paper, a group of researchers demonstrated that primate color vision has been selected to discriminate changes in skin color - those changes (like blushing) that give useful information about the emotional state of another. But does this mean that non-human primates feel shame? That's a harder question.

“The primate face and rump undergo colour modulations (such as blushing or blanching on the human face, or socio-sexual signalling on the chimpanzee rump), some of which may be selected for signalling and some which may be an inevitable consequence of underlying physiological modulations.”

Frans De Waal directs the Living Links Center at the Yerkes National Primate Research Center at Emory University in Atlanta. In his wonderful book The Bonobo and the Atheist (guess which of these he is), De Waal discusses emotional control among primates - and in particular, the role of shame. When a human feels shame after a transgression, "we lower our face, avoid the gaze of others, slump our shoulders, bend our knees, and generally look diminished in stature...We feel ashamed and hide our face behind our hands or "want to sink into the ground." This is rather like the submissive displays made by other primates: "Chimpanzees crawl in the dust for their leader, lower their body so as to look up at him or turn their rump towards tim to appear unthreatening...shame reflects awareness that one has upset others, who need to be appeased."

Only humans blush, De Waal writes, and he doesn't know of "any instant face reddening in other primates."

Blushing is an evolutionary mystery... The only advantage of blushing that I can imagine is that it tells others that you are aware of how your actions affect them. This fosters trust. We prefer people whose emotions we can read from their faces over those who never show the slightest hint of shame or guilt. That we evolved an honest signal to communicate unease about rule violations says something profound about our species. (The Bonobo and the Atheist, 155.)

And then De Wall makes a remarkable observation, one which seems to have first been observed in the Baraisa with which we opened:

Blushing is part of the same evolutionary package that gave us morality.

So it turns out that evolutionary biologists, psychologists, and social scientists, while they may disagree on some details, agree on one feature of the emotion of shame. It is a vital emotion for any ethically sound society. Which is precisely what we learned in this daf:

ומי שאין לו בושת פנים בידוע שלא עמדו אבותיו על הר סיני

And if a person is not [the kind of person who is] embarrassed - it is known that his ancestors did not stand and Mount Sinai.

[See also Talmudology on Ketuvot 67b, from where some, but not all, of this post is taken.]