The opening Mishnah of Masechet Rosh Hashanah includes this:

ראש השנה ב ,א

באחד בשבט ראש השנה לאילן כדברי בית שמאי בית הלל אומרים בחמשה עשר בו

On the first of Shevat is the New Year for the tree; [the fruit of a tree that was formed prior to that date belong to the previous tithe year and cannot be tithed together with fruit that was formed after that date;] this ruling is in accordance with the statement of Beit Shammai. But Beit Hillel say: The New Year for trees is on the fifteenth of Shevat.

Declaring different kinds of New Years goes back to the Talmud. But this practice was updated in a remarkable way by a Russian Jewish immigrant to the US in the early twentieth century. Tonight, we mark the fifteenth of Shvat, the date that, according to Bet Hillel, is the new year for the tithing of trees, and we will tell his remarkable - and overlooked - story.

“Twice a year on the fifteenth day of Shevat and on the eighteenth day of Iyar all the Jewish children from 3 to 13 years of age should undergo a thorough physical examination by the local Jewish physicians free of charge. ”

Charles Spivak and the fight against tuberculosis

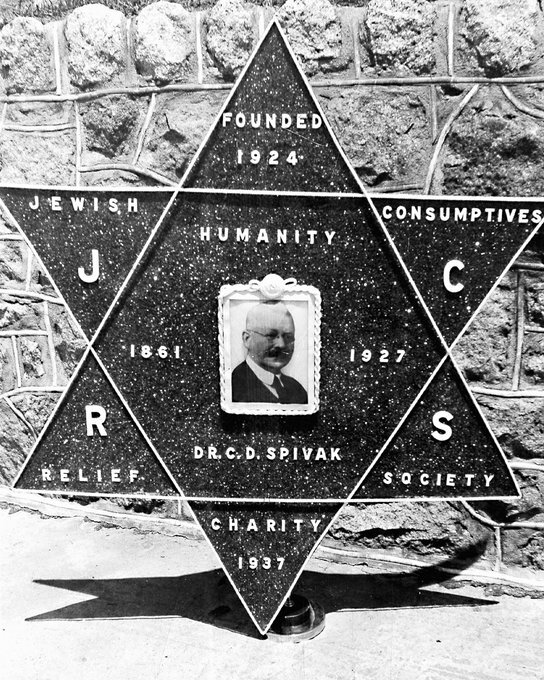

Hayyim Haykhl Spivakovski (1861-1927) immigrated to the US from Russia, where he became Charles Spivak. He graduated from Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia in 1890 (and his thesis, on talmudic theories of menstruation won a prize), and after his wife contracted tuberculosis in 1896 he moved with her to Denver. There she could take advantage of the high altitude which had been shown to help fight the disease. This began his life-long mission to fight the tuberculosis and improve the care of the many Jewish refugees from eastern Europe who contracted it.

From here.

Spivak founded the Jewish Consumptives’ Relief Society (JCRS), which provided kosher food and a Sabbath atmosphere, but was open to anyone. “We have in our institution chasidim and agnostics,” he wrote in 1914, “Jews and Christians, republicans and progressives, socialists and anarchists, men of all kinds of religious, political and economic options.” Spivak’s personal philosophy was informed by “a unique blend of Yiddishkeit [Jewish values], secularism and socialism” and his approach to the distribution of funds was sometimes at odds with bureaucratic and impersonal ways that some Jewish charities functioned. “We may not be able to return him [the patient] to his family as a useful working unit,” he reminded his benefactors, “we may actually waste money without any hope for any return, nevertheless, we feel that he or she must receive our care and attention, that whole-souled and whole-hearted charity is, after all, the only true, pure and unalloyed charity.” He estimated that of among the 3.3 million Jews then living in the US about 4,600 died each year from the disease, and ten times that number were chronically infected, or as he put it, were “living tuberculous Jews.” It was therefore the duty of the Jewish community to support the fight for to prevent the spread of tuberculosis and search for a cure.

Dr. Chales Spivak. From here.

In that opening Mishnah of Rosh Hashanah, we read that are several different dates that mark the beginning of different new years. The first day of the Spring month of Nissan is the new year for kings, which is used to date legal documents. The new year for trees is marked in the late winter month Shevat, which is used to count tithes, and first day of the late summer month of Tishrei is used to count the number of years since creation. In December 1918, Spivak updated this list and gave it a thoroughly modern twist. Writing in the Journal Jewish Charities, he suggested that the rhythm of the Jewish calendar could be used to improve public health and reduce the toll from tuberculosis.

Twice a year on the fifteenth day of Shvat (New Years for Trees) and on the eighteenth day of Iyar (Lag B'Omar) all the Jewish children from 3 to 13 years of age should undergo a thorough physical examination by the local Jewish physicians free of charge.

In the evening of the respective days all organized societies in the community should hold Health meetings at which the subject of how to maintain good health and prevent disease should be discussed by health officers and physicians.

A custom should also be inaugurated that all adults should visit their family physicians during the months of Tishre and Nisson [sic] for the purpose of undergoing a physical examination.

Spivak’s suggestion was of course dependent on a working knowledge of the Jewish calendar, but the dates he suggested would help. The fifteenth of Shevat was often celebrated in schools, and Lag B’Omer, the thirty-third day of the period leading up to the festival of Shavuot was celebrated as a minor holiday; it marked the end of the pandemic deaths of the students of the talmudic giant Rabbi Akiva. Most Jewish adults, even those who had jettisoned traditional Jewish practice when they arrived in America, would be aware of the timing of the other two months. The festival of Pesach (Passover) is celebrated in Nissan, and Rosh Hashanah, the start of the Jewish New Year that leads into Yom Kippur (the Day of Atonement) is commemorated in Tishrei.

Helping others, even after his death

Spivak, a member of the Denver Hebrew Speaking Society, developed liver cancer and died in 1927 at the age of 68. His generous spirit is evident in his last will and testament, where he asked that

…my body be embalmed and shipped to the nearest medical college for an equal number of non-Jewish and Jewish students to carefully dissect. After my body has been dissected, the bones should be articulated by an expert and the skeleton shipped to the University of Jerusalem, with the request that the same be used for demonstration purposes in the department of anatomy.

Apparently his request was fulfilled, and somewhere on the campus of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem is his skeleton.

Denver’s National Jewish Hospital

Spivak was not the only Jew who helped Denver’s many “consumptives.” He had traveled to Denver because of its high altitude, and in there in the 1880s a woman by the name of Frances Wisebart Jacobs raised funds to open a new hospital to treat the many “consumptives” who had traveled to the mile high city. She found support from the Jewish community, which agreed to plan, fund and build a nonsectarian hospital for the treatment of respiratory diseases, primarily tuberculosis. That hospital opened in 1899 as The National Jewish Hospital for Consumptives, and after several name changes it is now known as National Jewish Health. Today, it remains a major center for the care of patients with lung and respiratory illnesses.

““…[Pain] knows no creed, so is this building the prototype of the grand idea of Judaism, which casts aside no stranger no matter of what race or blood. We consecrate this structure to humanity, to our suffering fellowman, regardless of creed.” ”

While the Talmud declared four kinds of new year, Spivak declared a fifth. His new year for health was to be commemorated together with Tu B’Shavt, the new year for trees. In this way, he tied it to the Jewish calendar, and his memory is a reminder of the importance of getting a routine physical exam from your doctor. It might save your life.