In this page of Talmud the rabbis want to know why there were originally eighteen blessings recited in the silent prayer known as the Amidah. One rabbi suggested they correspond to the eighteen mentions of God in Psalm 29. Another thought they correspond to the number of times God’s name appeared in the Shema. But a third opinion was that they do not correspond to God’s name, but to something else entirely. A feature of human anatomy:

ברכות כח, ב

אָמַר רַבִּי תַּנְחוּם אָמַר רַבִּי יְהוֹשֻׁעַ בֶּן לֵוִי: כְּנֶגֶד שְׁמוֹנֶה עֶשְׂרֵה חוּלְיוֹת שֶׁבַּשִּׁדְרָה

…Rabbi Tanchum in the name of Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi said: They correspond to the eighteen vertebrae in the spine

Now this is all well and good, but didn’t Rabbi Tanchum know there are actually many more than eighteen vertebrae in the spine?

How many vertebraE are there in the spine?

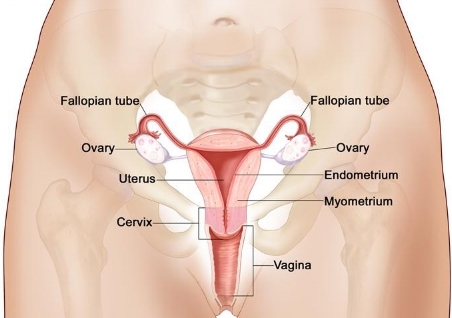

As you can see in the colored image, there are seven cervical vertebrae, and they end at the shoulders. Below these are twelve thoracic vertebrae, that end at the hips. Then come five lumbar vertebrae, which end at the sacrum, which itself consists of five fused vertebrae. And right at the bottom of your bottom is the coccyx, also known as the tail bone, which consists of three or five fused vertebrae, depending on how you count. That’s a total of 24 individual vertebrae and at least eight more that are fused. One thing is for sure: it’s not eighteen.

So How do we get to Eighteen?

The Koren English Talmud is sensitive to this anatomical conundrum, and explains that it is the number of vertebrae “in the spine beneath the ribs.” But the twelve ribs are attached to the twelve thoracic vertebrae, which would leave either seven vertebrae (five lumbar plus a sarcrum and coccyx) or thirteen to fifteen vertebra in various degrees of fusion. But not eighteen.

Here is the explanation of the Schottenstein (ArtScroll) English Talmud:“In stating the number of vertebrae in the spine the Rabbis apparently referred only to those below the neck. This accounts for seventeen vertebrae. The identity of the eighteenth vertebra mentioned here is unclear.” But that’s not quite right either. There are nineteen (12 thoracic and 7 lumber) spine below the neck. Not eighteen. So that doesn’t work.

We get closer to a plausible explanation when we read the commentary of the ArtScroll Hebrew Talmud. Here it is, in free translation:

In the language of the Rabbis, the word “spine” (שדרה) does not include the entire vertebral column, because the vertebrae in the neck are counted separately in the Mishnah (Ohalot 1:8). The Rabbis count of eighteen vertebrae apparently includes the back [thorax], the hips [lumbar] and one additional vertebra, either in the neck or in the base of the spine…

In other words, perhaps the rabbis of the Talmud saw the division of the spine in a different way than we do today. Just because we count seven cervical vertebrae this does not mean that is the number that others before us counted. Just ask Leonardo DaVinci.

“We can see a clear progression in terms of the accuracy with which da Vinci’s anatomical drawings were developed and how his drawings were influenced by his mindset, not just as an anatomist but also as an engineer and scientist; and to some extent, by the prevailing scholastic views at that time. His anatomical depictions were clearly far ahead of their era and have served to improve our understanding of the true anatomy and function of the vertebral column and spinal cord.”

The Spine in Leonardo’s Drawings

The way that the great anatomist Leonardo da Vinci (d. 1519) drew the spine evolved over time. In a 2017 paper on da Vinci’s depictions of the human spine, the authors note that in an early sketch “he may have used his knowledge of engineering to devise a concept that would functionally fit the movements of which the cervical spine is capable rather than trying to illustrate the exact anatomical detail.” They continue:

The vertebrae are portrayed in a rudimentary manner, many lacking a foramen to convey the neurovascular supply, an intervertebral disc, or the spinous process necessary for muscular insertion and rib articulation in the thoracic spine. It may be better to view this depiction as a conceptual illustration of how the structure accommodates its function.

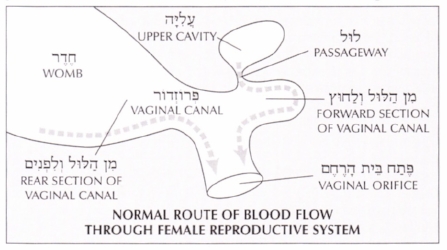

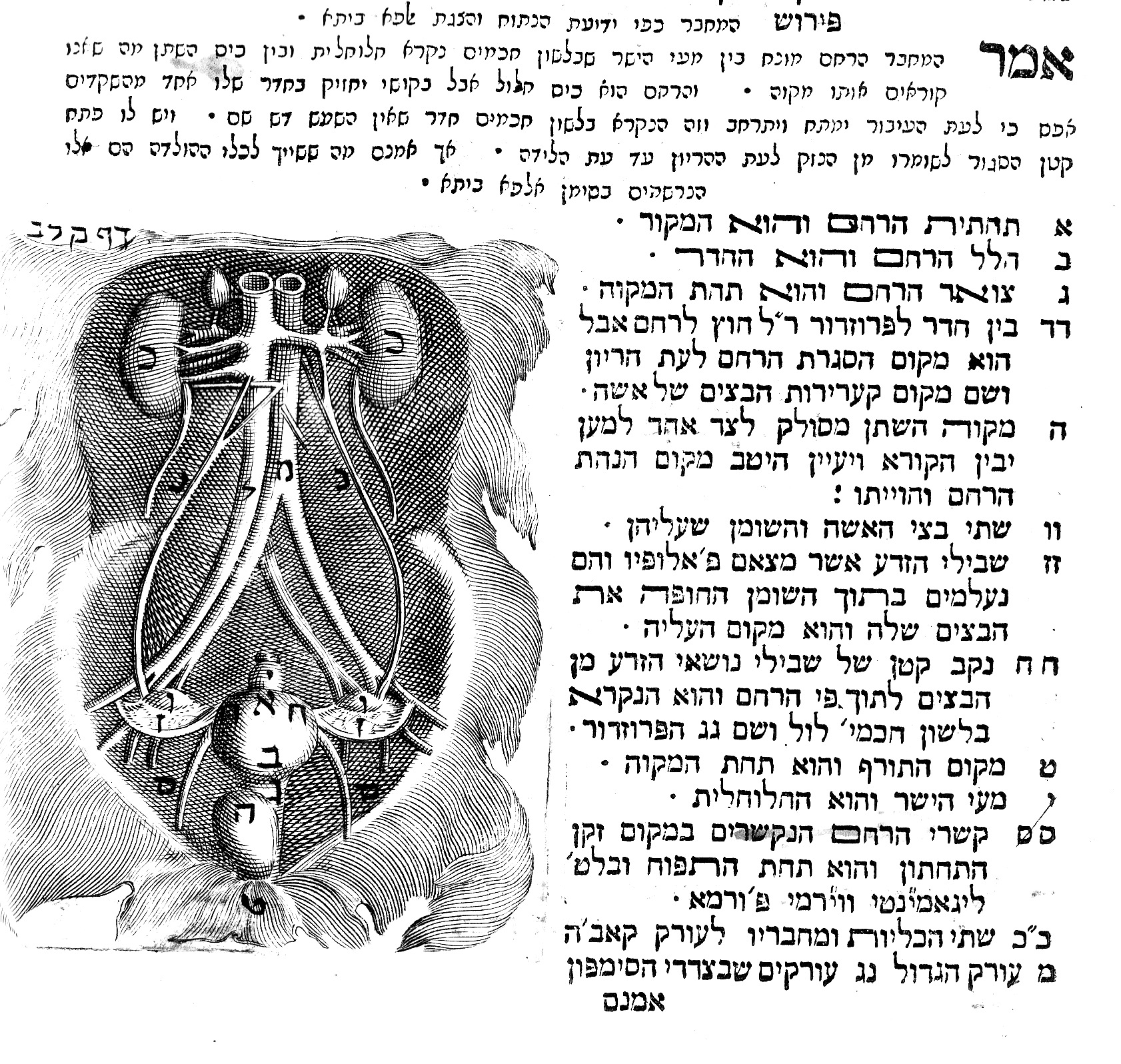

Just take a moment to count the number of vertebrae in the neck that Leonardo drew below.

That’s right. There are thirteen! That can’t be right! Because of these clear inaccuracies the authors wrote that this drawing was made prior to Leonardo’s any dissection of the anatomical region in question. (By the end of his life Leonardo claimed to have dissected thirty human bodies, as well as those of countless sheep and oxen.)

Now take a look at the drawing below, made later in Leonardo’s career, which is much more anatomically accurate. But as you can see, there is no obvious place to end the cervical vertebrae and start the thoracic. Or end the thoracic and start the lumbar. It’s just one one long beautiful anatomical structure.

Leonardo da Vinci. The vertebral column c.1510-1. Detail of the first accurate depiction of the spine in history, with its distinct sections and curvatures all correctly shown. From the Royal Collection Trust.

Leonardo suggested a division of sorts which are shown by the thin lines, one of which is labeled with the shape of a “d.” Take a look at the same Leonardo image, with the count of the number of vertebrae in between each division added.

As you can see they add up to 18 if you count the spines of the vertebrae. But there is one missing vertebrae, the very first one at the top of the neck. Take another look. See it? It is called the atlas, and its unique feature is that it has no spinous process, as you can see below:

The first vertebra, known as the atlas.

The atlas is the first of what we count as the seven cervical vertebrae. But it looks very different from the other six below it.

So if you don’t count the vertebrae without a spinous process - and it is very different from all the other (unfused) vertebrae - then you don’t need to look for the missing vertebra. It never got lost. We just started our numbering based on a different criteria. Why on earth would the rabbis have counted seven cervical vertebrae as we do, rather than six or even eight? (And yes, I know there is this Mishnah that states there are eighteen vertebrae, eight of which are in the neck: “וּשְׁמֹנֶה עֶשְׂרֵה חֻלְיוֹת בַּשִּׁדְרָה…שְׁמֹנָה בַצַּוָּאר.” But read it agin. It does not appear to be actually counting only bones.)

Leonardo’s anatomical drawings is a reminder that the human body has been seen and dissected in different ways, and Rabbi Tanchum’s count is as precise as our own. Different, but precise.